What Is the Rarest Chicken in the World?

After six weeks of designer runway shows, the last thing fashion people want to do is go to a fashion party. So it was a surprise when, in early April–less than a month after Paris Fashion Week–crowds of fashion insiders flocked to a penthouse suite on the 43rd floor of the Trump SoHo for a cocktail hour hosted by luxury fashion marketplace Farfetch, the online retailer that today announced a $66 million Series D round of funding led by private equity firm Vitruvian Partners, with contributions from existing investors Conde Nast and Advent Ventures, as well as new investor Richard Chen from Chinese VC firm Ceyuan.

But there was no talk of round-raising that evening. The event constituted the welcoming reception for Farfetch's annual consortium, where boutique owners from across the U.S. gather for two days of discussion centered on one problem: how to sell more clothes on the Internet. "It's a great time for them to meet face-to-face with the team," said Farfetch founder José Neves the morning after the conference. "And it's a chance for them to share."

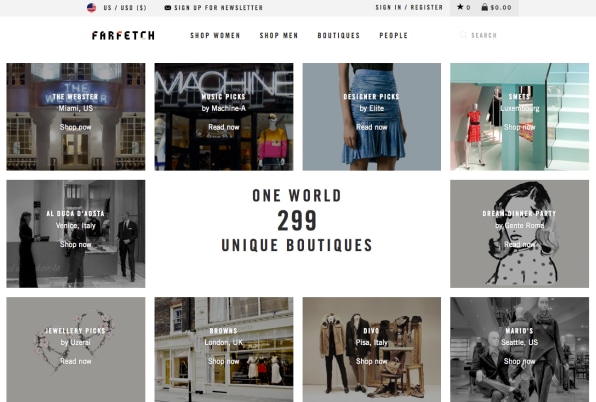

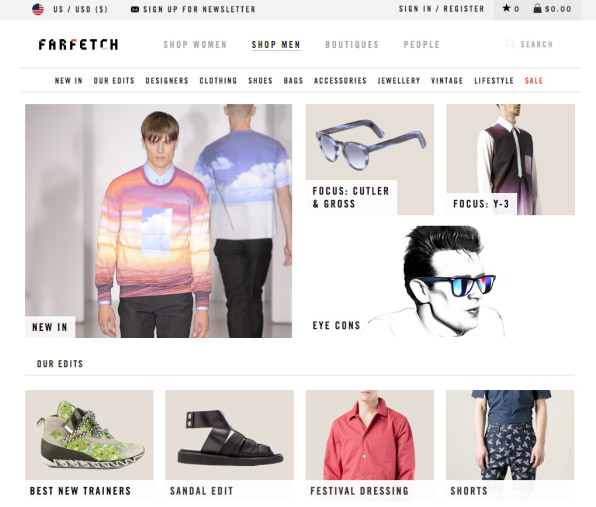

A serial entrepreneur, Neves launched the London-based company in 2008. Like its competitors Net-a-Porter or Moda Operandi, Farfetch enables customers to shop by designer, product type, color, size, etc. Unlike its competitors, Farfetch itself does not hold inventory. Instead, it runs the e-commerce outfits of 300 independent boutiques. The Webster in Miami, D'NA in Saudi Arabia, and Anita Hass in Hamburg are all part of Farfetch: individually, these names might not mean much to the pedestrian luxury shopper, but collectively, they represent more than 100,000 units of hard-to-find pieces, such as a $1,228 lattice-detail top by Christopher Kane (from Smets in Luxembourg), or a $13,605 backless dress by Alexander McQueen (available from Paris's Montaigne Market.) Though department stores and digital-native outlets throw cash into search engine optimization and digital marketing, most independent retailers will never match the big players in that realm. For the boutique owner, therefore, Farfetch offers a way to crack the Internet.

In addition to providing a global platform–30% of sales on Farfetch are to customers in the U.S., but the site has plenty of shoppers in Europe, Asia, and South America, as well–Farfetch also handles customer service on behalf of its client boutiques, and offers an easy-to-use management system to track orders. (Farfetch even pays for retailers' stock to be photographed, in order to maintain a consistent look on the site.) Boutiques are responsible for shipping their own orders, although Farfetch has worked out deals with major delivery services so that costs aren't exorbitant, no matter how many miles a package is traveling. Farfetch's account managers, who typically handle around 10 accounts at a time, are tasked with keeping store-owners happy, and also recruiting new stores into the Farfetch portfolio. The company will court boutiques for several years if it feels the fit is right.

The marketplace business model is not original, but it is effective, and venture capitalists are particularly bullish in that area thanks to the success of Etsy, eBay, and Amazon. Since 2010, Farfetch has raised $44 million from firms including Index and e.ventures, as well as Conde Nast. It's used some of that for technology upgrades–in a past life, Neves was a software programmer, so he prides himself on his site's advanced back end–but more to bulk up its executive roster. Neves brought in eBay alum Andrew Robb as COO in July 2010, Net-a-Porter alum David Lindsay as SVP of technology last February, and Gabrielle de Papp from Neiman Marcus as VP of U.S. brand and business development last June. Even more recently, he brought on Giorgio Belloli–a veteran of Alexander McQueen and Prada–as his chief commercial officer, and Stephanie Horton–a former Vogue marketing exec, who was most recently head of global communications at Shopbop–as his CMO. Horton, an American, picked up and moved to London in August, after Neves persuaded her to come aboard.

"I'm really not that person to be convinced to go and do something like that," she said on a call from the Dubai, where Farfetch was hosting a dinner for local influencers. (Her next stop: Kuwait.) "But Jose is an excellent advocate. His belief is contagious."

Neves–and his investors–have big plans for Farfetch. While the company won't reveal its latest sales figures, it will say that those numbers have doubled over the past year. Annual sales have reached $275 million, with a year-over-year growth rate of 100%. The site averages about 7 million pageviews each month–bigger than many fashion editorial properties–and the average order is a steep $650. In January, the site celebrated its first $2 million day. There are plans in the works to release Japanese, Chinese, and Russian-language versions of the site to appeal to the growing customer base in those countries.

The goal? Make Farfetch less of a traditional marketplace and more of a brand in its own right. Along with dinners and events aimed at influencers–bloggers, big spenders, editors–in markets Farfetch would like to further engage, the site recently sponsored the premier of Gia Coppola's directorial debut, Palo Alto, at the TriBeCa Film Festival. "Farfetch has a big story–it's a great site with amazing merchandise from boutiques–but it's a lot to tell," Horton said at the annual meeting in New York. "Our biggest challenge is trying to explain the concept in a clear, concise way." Added Belloli, "The goal is to turn Farfetch from a service provider to a brand."

But Neves must walk a fine line. Without his individual boutiques, there is no product. In many ways, he needs them more than they need him–Farfetch takes an average 25% commission on each item sold according to retailers who have either worked with Farfetch or been in talks to do so, figures the company itself will neither confirm nor deny–which is why these store-owner get-togethers are so crucial to the business. Along with addressing concerns and patting egos, Neves wants to make retailers see Farfetch as a second location for their stores, rather than just an online funnel for merchandise. Many boutiques simply post the inventory they already have on Farfetch, but others are now buying pieces specifically for the site. "It's allowing them to buy in much more interesting ways," Belloli said. "We're getting them to think more about a global customer."

Brian Bolke, owner of Dallas's highly regarded Forty Five Ten–which joined Farfetch in September 2013 after two years'-worth of conversations–confirmed that the partnership has broadened his customer base. "We initially spent a lot of money, time and effort on our own e-commerce. It was connecting with our local clients, but not internationally," Bolke said. "We tend to buy only one or two of something very, very special, and it has finally caused a sense of urgency. There were women who thought, 'I'm probably the only woman in Dallas who would buy this." And now they aren't. They realize they have to act."

There are still indie retailers that prefer to operate their own e-commerce sites, or eschew online sales altogether like Ikram in Chicago, whose owner is best known for styling Michelle Obama in her early White House years. Farfetch's business development team will undoubtedly spend lots of time attempting to woo them. But no matter: its current partners are blazingly confident about the site's future. At Kirna Zabete in SoHo, owners Sarah Easley and Beth Buccini have hired a dedicated employee to handle Farfetch orders, with another working on it half-time. The duo originally launched e-commerce in 2008–early for an indie–and still operates its own boutique on kirnazabete.com. Business had been steady, but Easley and Buccini nevertheless felt compelled to join Farfetch in July 2013. "It's been absolutely amazing for us," Buccini said at the party in the Trump penthouse. "Our web sales are up 138% this quarter." If Neves can do the same for each of his boutiques, the sky's the limit–or at the very least, for the time being, the rooftop pool.

What Is the Rarest Chicken in the World?

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/3029848/like-a-high-fashion-etsy-farfetch-puts-the-worlds-rarest-fashion-at-your-fingertips

0 Response to "What Is the Rarest Chicken in the World?"

Post a Comment